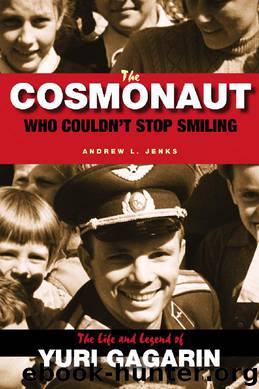

The Cosmonaut Who Couldn't Stop Smiling: The Life and Legend of Yuri Gagarin by Andrew L. Jenks

Author:Andrew L. Jenks [Jenks, Andrew L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Northern Illinois University Press

Published: 2012-05-15T06:00:00+00:00

Chapter Seven

HOMO SOVIETICUS

If Gagarin’s image reflected anxieties about Russia’s place in the modern world, it was also shaped by his own behavior. In his role as the potted, official Soviet icon Gagarin personified the self-sacrificing romanticism of the Soviet hero. But then there was another Gagarin: the Russian Soviet celebrity who conveyed the materialistic, hedonistic, solipsistic spirit of an emerging consumer society. When the Soviets put out a line of Gagarin chocolates with images of Gagarin on the wrapper they made literal the transformation of Gagarin into a consumable commodity. Gagarin, in short, was part of the first “me” generation in Soviet socialist society, a narcissistic consuming “I” in a collectivist “we” system.

Nowhere was that contradiction more evident than in Gagarin’s role as the founder and first head of the Soviet water-skiing association. It was a sport that Gagarin believed was appropriate for future patriots and military officers: honing the reflexes, toning the muscles, integrating machine, man, and the natural elements. But it was also just fun as hell to take off one’s shirt and preen for the pretty ladies—a seemingly bourgeois pursuit that Gagarin said caused some stodgier Soviets to accuse him of “dandyism.” He said he “even heard from some [critics] that water-skiing is supposedly the latest fad coming from the West,” which of course it was.1

The same tension was also reflected in Gagarin’s love affair with the motor car. After Gagarin died, his official black Volga, which his father thought was a “real car,” was enshrined in a glass case outside the Gagarin museum in the city of Gagarin (so renamed right after his death). Yet it was a fancy red fiberglass Matra Djet, a banner of capitalist self-indulgence given to him as a gift from the French people, that the historical Gagarin really loved to drive—at excessively high rates of speed, gleefully terrifying friends and family during joyrides. His father derisively called it “that frog thing.”2

Gagarin’s curious hybrid of the official Soviet hero and the modern celebrity (capitalist or communist) made him potentially attractive to a variety of constituencies, from testosterone-driven males and swooning teenage girls to Russian nationalists and party moralists. It also reflected a fundamental change in Soviet society since Stalin’s death. More than just aspects of his personal biography, the many strands of Gagarin’s post-flight life convey the paradoxical essence of the male Homo sovieticus in the 1960s: someone who combined selfless service to state and nation with the tireless pursuit of pleasure and leisure.

Consumer Identities and Secret Cities

Unlike many shadowy figures in the Soviet military-industrial complex, Gagarin could reveal himself as a public figure. But he could also retreat to the inner sanctum of Soviet power to escape public scrutiny, much as a chauffeured Hollywood star might disappear behind the guarded gates of his or her manse. Coming from a secret place lent an aura of mystery and glamour to Gagarin’s celebrity; it also gave the first cosmonaut a heady sense of empowerment. When an official ceremony preceded Valentina Tereshkova’s flight (June

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| France | Germany |

| Great Britain | Greece |

| Italy | Rome |

| Russia | Spain & Portugal |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26584)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23062)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16837)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13294)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7105)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5490)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5077)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4941)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4793)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4790)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4449)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4340)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4239)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4177)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4082)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4011)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3944)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3623)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3451)